Medical research is falling behind the burden of disease because medical education is not effectively bridging the gap between research and clinical practice. That's the stark appraisal of three Oxford-based researchers, including Oxford University’s head of medical sciences.

In an article for journal Science Translational Medicine, Dr Alastair Buchan and colleagues Gabriele DeLuca and Pavel Ovseiko call for a new approach to training what are called clinician-scientists, doctors educated both as medical practitioners and researchers.

They say that the current approach to medical training means that the development of clinical skills and knowledge is increasingly separated from education in research skills and knowledge. Training in the two areas is not only separated by teaching timetables that see the two areas as firmly discrete and disconnected but by the increasing move of research from hospitals to specialist centres.

In the paper they say: 'Many medical school labs that previously focused on clinical teaching and clinical investigations have moved out of hospitals to purpose-built institutes and research centres that focus on basic sciences.'

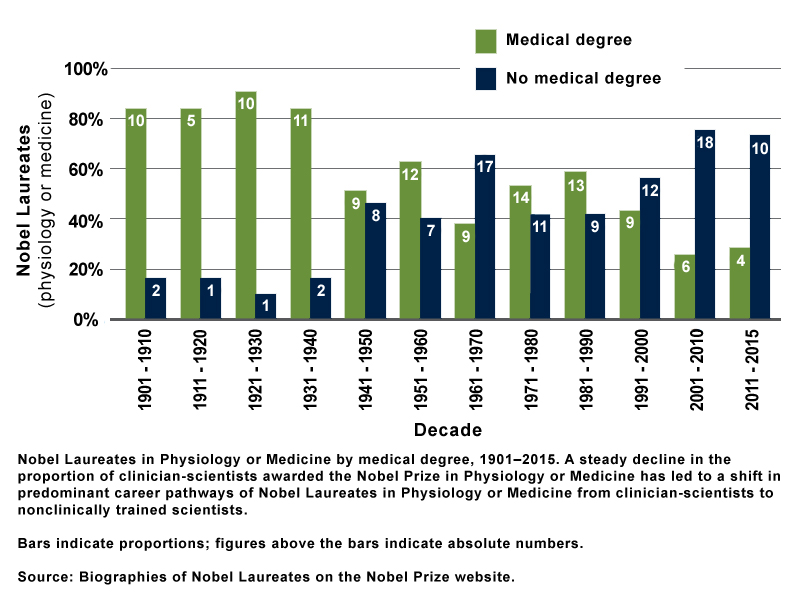

This shift is reflected in Nobel Prize awards: Until 1960 the Nobel Prize for Medicine was mainly awarded for discoveries in human disease; since then it has gone to people making discoveries in basic molecular biology and genetics. The writers say: 'The downside of this shift is that most basic science discoveries have yet to be translated into therapies and improved patient care, while the burden of chronic disease associated with the 21st century's aging population is escalating.'

They believe that there needs to be more focus on translational research – taking basic science and turning it into practical and effective treatments for health problems. Clinician-scientists are particularly suitable in this area as they are well placed to be translators with their understanding of the language, culture and latest discoveries and issues in both medical practice and medical research.

The authors warn that it is difficult to successfully train to work in both areas, as degree courses are longer, incurring higher debts, and more intensive, placing strains on students that result in higher drop-out rates. They advocate a change to medical training that sees students selected for clinician-scientist training and given more flexibility to personalise progress through the medical curriculum to allow time for research that is linked to what they are learning in their medical training.

That personalised approach would be backed by close mentoring and a renewed focus on teaching, they say: 'The stale but pervasive view that educators are failed clinicians or scientists requires dismantling.'

By bringing together training in the lab and on the ward, they say that this would encourage scientific innovation for patient benefit and ensure medical schools are turning out graduates better poised to overcome the medical challenges of this century.