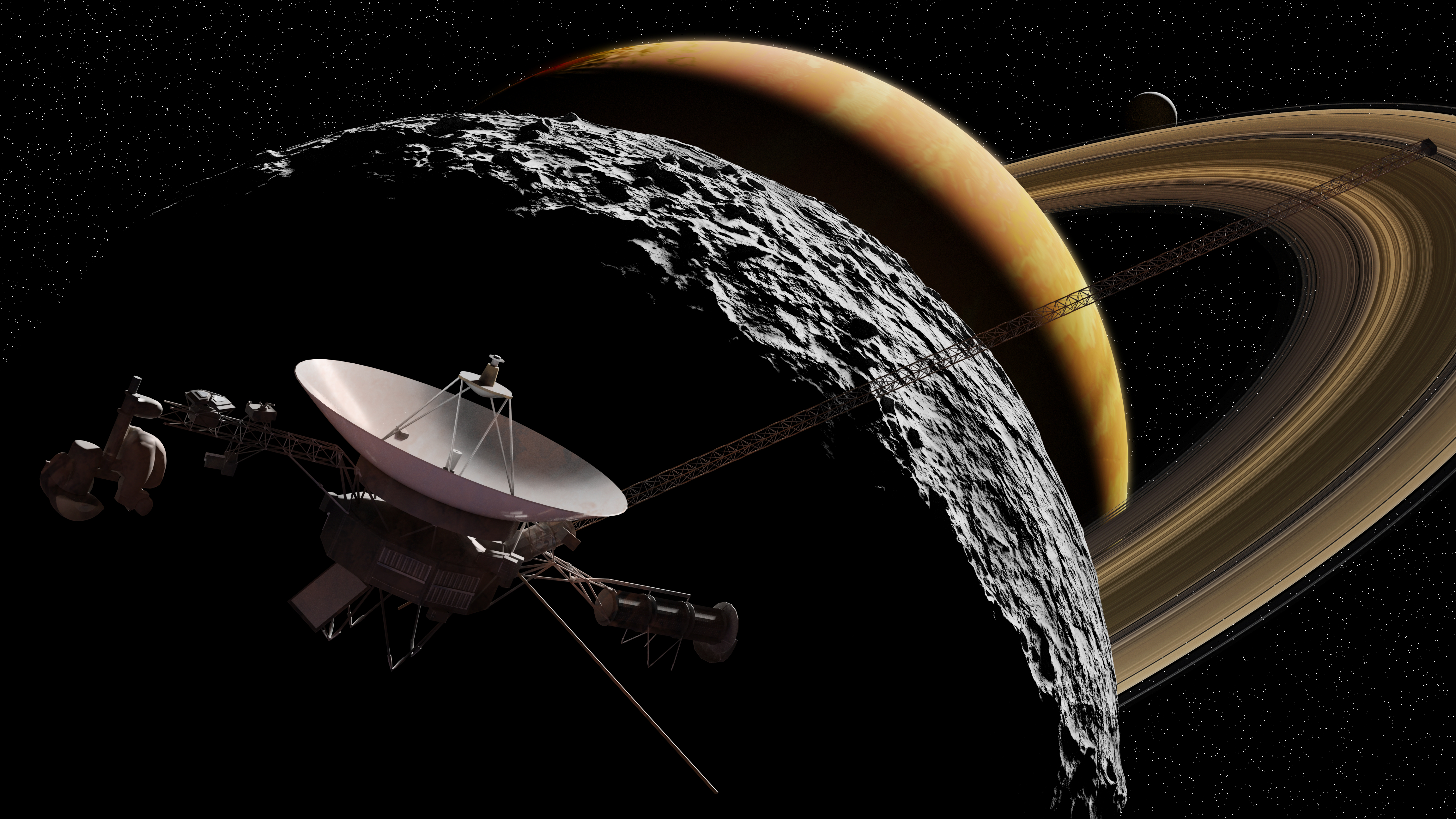

Oxford University scientists are today mourning the demise of the landmark Cassini Space Mission, launched almost twenty years ago.

The probe will end its journey with a momentous suicide dive on Friday 15 September. When the spacecraft runs out of fuel, it will shatter into fragments and implode into Saturn’s atmosphere.

Led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the original Cassini mission launched in October 1997. Scientists from the Department of Physics at Oxford University and RAL Space in Didcot have played an integral role in the satellite’s creation from the start. The group built some of the probe’s most significant components and even witnessed history when they attended its launch at Cape Canaveral.

Since leaving Earth twenty years ago, Cassini has ushered in a new age of science, delivering valuable high quality data that, as the first spacecraft to orbit Saturn, has allowed unparalleled insight into the planet’s activity.

The joint US and European Cassini-Huygens mission is the most complex and ambitious unmanned space expedition in history. It has informed scientists' understanding of Saturn’s structure and atmospheric make-up, including the realisation that the planet actually has sixty two moons – twenty more than first thought.

Together with losing a key unique stream of data I will miss the camaraderie of the international Cassini/CIRS team and will miss being able to look up at Saturn and think ‘I helped build something in orbit about that!’

Dr Patrick Irwin, Professor of Planetary Physics at the Oxford University Department of Physics

Scientists from Oxford were involved in the construction of one of the mission’s main instruments, the Composite Infrared Spectrometer or CIRS. Led by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, CIRS measures the heat emitted by a planet’s atmosphere or surface and identifies the individual elements present in the minerals and gasses, revealing their chemical make-up.

The Oxford team provided two critical structural elements of the Cassini probe: the radiative cooler, which is the radiator that sits on the side of the spacecraft, cooling the CIRS infra-red detectors to -190C; and the mid-infrared focal plane assembly, which holds the infrared detectors and focuses the light from the instrument’s main telescope, a bit like the lens of an eye.

The Oxford University Department of Atmospheric Physics has played a key role in interpreting the spacecraft’s observations of Saturn and its largest moon, Titan. Oxford physicists used data gathered by CIRS to explore and understand storms, vortices and waves in both Jupiter and Saturn’s atmosphere, detecting and quantifying seasonal cycles of temperature and photochemically produced molecules in Titan’s atmosphere.

Led by Dr Simon Calcutt of Oxford’s Department of Atmospheric Physics, the team included Dr Patrick Irwin, Professor of Planetary Physics (who went on to lead the scientific analysis effort), Dr Neil Bowles, University Lecturer, and Dr Jane Hurley, previously a Post-Doctoral Research Associate at Oxford, and now Project Manager at Science and Technology Facilities Council RAL Space.

Acknowledging the bittersweet culmination of two decades of work, Dr Patrick Irwin, said; ‘Cassini/CIRS has provided the underpinning to our planetary research in Oxford, and during its 20-year mission we have grown older, raised families and trained a whole new generation of scientists who have gone on to be international leaders of planetary science in the Europe and the USA.

‘Speaking personally, the Cassini mission is as old as my marriage, which took place two months before the launch, and I and my wife were lucky enough to witness the launch in 1997. Together with losing a key unique stream of data I will miss the camaraderie of the international Cassini/CIRS team and will miss being able to look up at Saturn and think ‘I helped build something in orbit about that!’ Our design, construction and testing of the CIRS cooler was a job bloody well done and it still amazes me what we achieved with relatively little resource.

‘Anyway, we’ll raise a glass, or two, in the pub to Cassini on Friday lunchtime and will remember our involvement fondly and with great pride.'

Dr Jane Hurley added; 'Cassini has provided the international science community with decades of irreplaceable insight into Saturn and its moons, and inspiration to generations of scientists and engineers. As part of both the CIRS instrument science team and operations team, I have been very lucky to be part of such a successful mission - not least because of the collaborations and working relationships that become lifelong friendships. I shall also toast the Cassini/CIRS operations team in the UK, Europe, at NASA/Goddard and NASA/JPL for the years of hard work behind the scenes that have given us the mission we’re celebrating today.’

During its final dive Cassini will be travelling at around 70,000mph. Its plunge to destruction will mark the end of a series of 22 orbits, as the probe becomes the first ever to slip between Saturn and its rings.

Because Saturn is so far away, the spacecraft's final transmissions will take 83 minutes to reach Earth. As the final pieces of the probe burn away to nothing, the landmark mission’s legacy, of setting the gold standard for exploratory space travel, will live on long after the spacecraft itself.