As the second wave hits the UK, 15% of citizens are at risk of being less informed, uninformed or misinformed about COVID-19

A new report by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism looks into the 'infodemically vulnerable', a group that consumes little to no news about COVID-19, and would not trust it even if they did.

Most of the UK public are well informed about COVID-19, say they follow government guidelines and say they are willing to take additional measures if instructed to do so. However, a large minority of the public do not feel that the news media or the government have explained what they can do in response to the pandemic.

A substantial part of the population can be defined as ‘infodemically vulnerable’. The members of this group consume little to no news and information about COVID-19, and say they would not trust it even if they did. They have grown from 6% early in the crisis to 15% by late August – an estimated 8 million people who are more at risk of being less informed, uninformed or misinformed about the disease. These are the main conclusions of Communications in the coronavirus crisis: lessons for the second wave, a new report published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. The report, authored by Rasmus Nielsen, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, and Felix M Simon, is based on an online panel survey of a representative sample of the UK population at regular two-week intervals. The surveys, designed by the Reuters Institute and fielded by YouGov, are part of the UK COVID-19 news and information project, an initiative funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

How did we conduct our research?

The project analyses how the British public navigates information and misinformation about coronavirus and how the government and other institutions are responding to the pandemic. It is based on a ten-wave online panel survey of a representative sample of the UK population. The survey was designed by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and was fielded online by YouGov between April and August 2020.

What did we find?

Most people are well informed. We gauged how informed people are about COVID-19 by fielding eight factual questions in August with one correct answer, several alternatives, as well as a 'don't know' option. A large majority of respondents (75%) answered most of the questions (five or more) correctly. Many respondents gave answers that are incorrect but err on the side of caution: for example, only 26% give the correct answer to the question on how long they should stay at home if they have symptoms (10 days) but 70% answered 14-21 days. Specialised jargon mostly unknown in February is now familiar to most – including 'antibody test' (77%) and ‘R0’ (86%).

Most people say they are cautious. When asked to describe their behaviour during the pandemic, almost half of our respondents say they are always following official guidelines and are taking measures like working from home, limiting contact with others, keeping two metres distance and washing their hands regularly. If we include those who answer 'most of the time', 90% or more say they follow most of these guidelines. The main variations are around social inequality – those with low income and low levels of formal education are much less likely to say they are working from home. However, it should be noted that these are self-reported data, and may not accurately reflect how people actually behave.

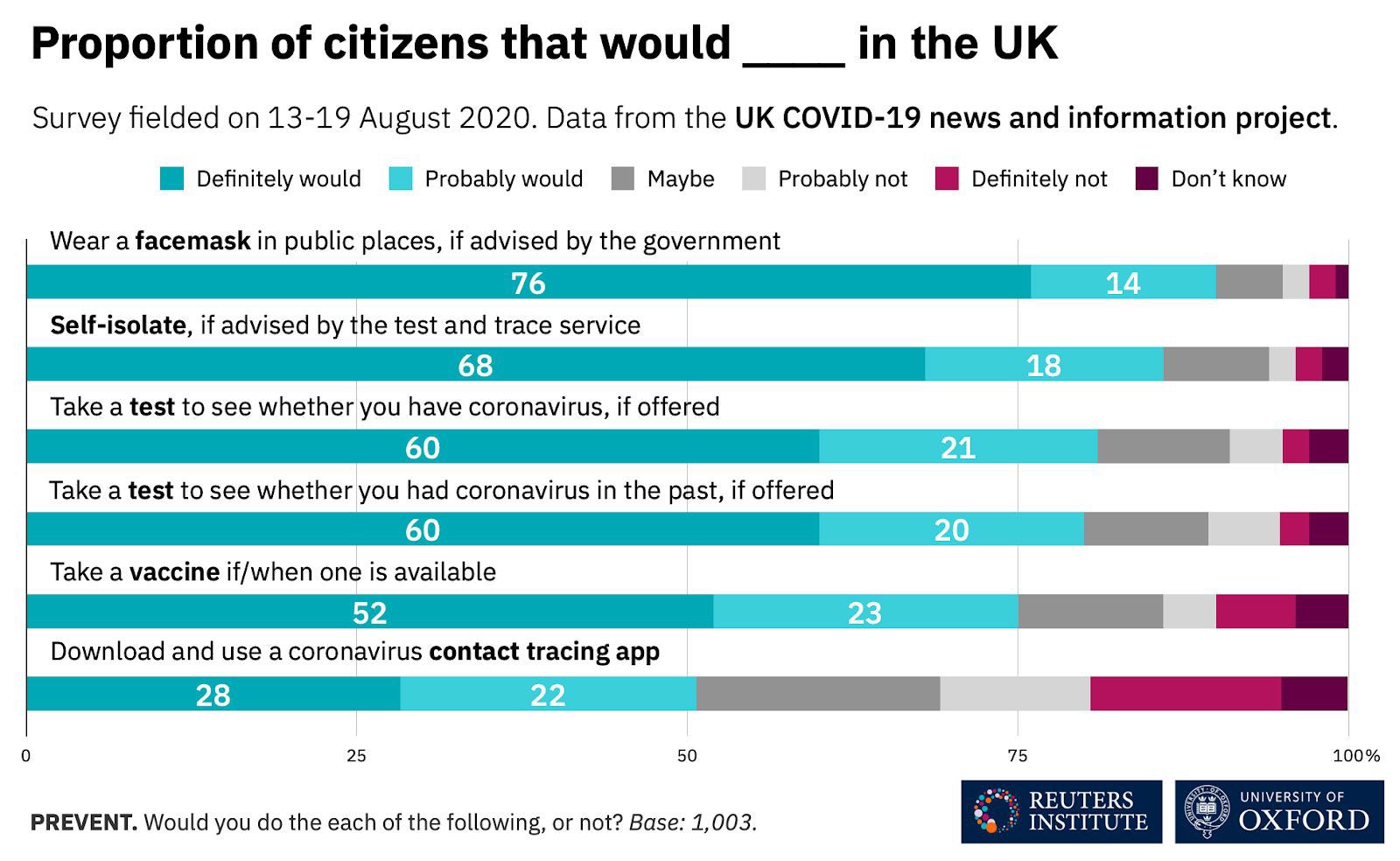

Most people are willing to take more measures. The public seems receptive to take additional measures to protect themselves and their loved ones. Between 75% and 90% of respondents say they definitely or probably would wear a mask in public spaces, self-isolate if advised to do so, take a test if offered and take a coronavirus vaccine if or when one is available. The main outlier is whether people would be willing to download the contact tracing app: in August only 28% said they definitely would do that with another 22% saying they probably would. It is important to note that these data measure people’s self-reported willingness to adopt certain measures in theory. In practice, people may find them difficult to adhere to strictly all of the time.

The proportion of UK citizens in August who said they would take specific actions related to coronavirus, including wear a facemask, self-isolate, take a test, take a vaccine or use a contact tracing app.

The proportion of UK citizens in August who said they would take specific actions related to coronavirus, including wear a facemask, self-isolate, take a test, take a vaccine or use a contact tracing app.The proportion of UK citizens in August who said they would take specific actions related to coronavirus, including wear a facemask, self-isolate, take a test, take a vaccine or use a contact tracing app.

A large minority don't feel the news media or the government have explained what they can do. In August, only 61% said the news media have 'explained what I can do in response to the pandemic' (down from 73% in April). 58% said the same about the government (down from 67% in April). This means about 20 million people out of the UK adult population of about 52 million do not feel that the news media or the government have explained what they can do.

Information inequality is a real problem. Our data shows systematic inequalities around age, gender, as well as income and education in how people engage with information about the coronavirus, suggesting that the ways people navigate the second wave and make sense of the often polarising responses to it will be even more marked by inequality than earlier parts of the crisis.

Which people are most at risk?

Trust in news organisations as a source of information about the pandemic has fallen 12 percentage points from 57% in April to 45% in August. COVID-19 daily news use has dropped 24 points over the same period, from 79% to 55%. Both declines suggest the emergence of the 'infodemically vulnerable', a group that both consume little to no news and information about COVID-19, and do not trust it even if it reaches them.

The report identifies this group as the subset of the respondents in each wave of the survey who say both that they consumed COVID-19 news less than once a day on average from news organisations and that they have low trust in COVID-19 news from news organisations.

The report provides a first estimate of the size of this group, which has grown from a small minority of 6% early in the crisis to a significantly larger minority of 15% by late August –an estimated 8 million people who are more at risk of being less informed, uninformed or misinformed about the disease. Just as epidemiologically vulnerable individuals do not necessarily fall ill, but are more at risk, the infodemically vulnerable are not necessarily misinformed or uninformed, but they are more at risk, because they do not use and do not trust news (which previous research has demonstrated is associated with a better understanding of the coronavirus).

The infodemically vulnerable group is roughly evenly split by gender, but there are differences by age and education. By August, those under 35 were more likely to be in the group (20%) than those aged 35 and over (14%). Similarly, those that were educated to degree level (11%) were less likely to be vulnerable than those that were not (18%).

What can be done?

The report explores the best ways to reach the 'infodemically vulnerable' and help them make the best decisions about the pandemic. The BBC is the most widely used news source in this group. They are also more likely to use social media such as Facebook and Twitter than those that were not vulnerable, and might also be reached via these platforms, though it is important to note that public trust in COVID-19 information found via platforms is low. The report suggests the best way to communicate with the broad public in the next stages of the coronavirus crisis is to focus less on politicians and pundits and more on the sources that are highly and broadly trusted, and demonstrably help people understand the crisis, most notably the NHS and scientists, doctors, and other experts.

Read the full report or explore the Reuters Institute's UK COVID-19 news and information project.

The University of Oxford's vaccine development work

Our vaccine work is progressing quickly. To ensure you have the latest information or to find out more about the vaccine trial, please check our latest COVID-19 research news or visit the COVID-19 vaccine trial website.