Water insecurities – from not having sufficient water for drinking or irrigation, to being exposed to water-related hazards like droughts and floods – are distributed unequally across geographies and socioeconomic contexts. The ways in which people experience these water insecurities in their daily lives are shaped by intersecting social identities, usually around the axes of gender, wealth, ethnic groups, and others.

Dr Sonia Ferdous Hoque, Dr Catherine Fallon Grasham and Dr Marina Korzenevica

Water insecurities – from not having sufficient water for drinking or irrigation, to being exposed to water-related hazards like droughts and floods – are distributed unequally across geographies and socioeconomic contexts. The ways in which people experience these water insecurities in their daily lives are shaped by intersecting social identities, usually around the axes of gender, wealth, ethnic groups, and others.

By amplifying water-related shocks and seasonal variations, climate change is exposing the cracks in society that make some individuals or groups more vulnerable than others. Since 2015, REACH’s research has generated a wealth of evidence from Ethiopia, Kenya and Bangladesh on the unequal ways in which climate and water-related risks affect everyday lives.

The daily experiences of water-related climate vulnerabilities

Recognising the nuanced and context-specific experiences of climate shocks is crucial to understand how and why certain groups are vulnerable. Here, we reflect on the everyday experiences of climate risks affecting drinking water access, livelihoods and vulnerability to extreme events, and how they are differentiated across wealth, space, and gender.

Increased costs of accessing drinking water

From the parched landscape of semi-arid Kenya to the coastal floodplains of Bangladesh, drinking water challenges intensify during the dry season. People’s ability to cope with these seasonal and spatial variations are often shaped by their wealth status.

While wealthier households can invest in private wells and rainwater tanks or afford to purchase costly vended water from distant sources, poorer households resort to low quality sources, walk longer distances, or ration their use to cope. With their socially defined roles as household ‘water managers’, women and girls are

Climate change is aggravating the financial challenges caused by seasonal variabilities. Evidence from rural Kenya shows that delays in onset of the rainy season can increase household expenditures for water. Meanwhile, heavy rainfall can pose a financial risk to the sustainability of water supply systems. This is due to a decrease in revenue from user payments, when users seek alternative rain-fed sources which are freely available.

In southwestern Bangladesh in 2020, cyclone Amphan damaged embankments and contaminated freshwater sources with saline water. This resulted in additional repair costs, that were passed on to water users during a time when people’s livelihoods were already constrained by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Livelihood impacts and coping capacities vary by location and wealth status

Agro-pastoral livelihoods are vulnerable to geographical and seasonal differences in water availability. In Ethiopia’s Awash Basin, while subsistence farmers in the arid lowlands face risks of water scarcity for irrigation, those in the wetter upstream regions suffer from flooding and pollution from urban areas and industries. During the 2015-16 drought, water-intensive private sector operations, such as flower farms, having finances to access groundwater resources were more resilient than small farmers relying on irrigation canals fed by rainwater.

Similarly, large farmers in coastal Bangladesh can recover from aquaculture losses caused by cyclones through increased investments in the next season. However small farmers may need to sell assets and migrate elsewhere to make a living.

Experiences of extreme events are shaped by intersecting social identities

The impacts of water insecurities are gendered, due to differences in social roles and access to assets by men and women. In the Awash Basin, for example, men reported feeling angry or weak as a result of being unable to provide for their families during floods or droughts, or worried about conflicts over rangelands for livestock fodder. On the other hand, women expressed concerns about rising food prices and being unable to feed their children, and suffered from an increased workload for collecting water.

In the arid town of Lodwar in northwest Kenya, the extreme poor often continue to live in flash flood-prone areas by the Kawalase River. Relocating to alternative land can be impossible, as it requires access to funds and/or support from the NGOs – which are often dependent on connection to local powerful clique. In addition, moving outside the town boundary means losing access to markets, making it particularly difficult for women to generate their own income.

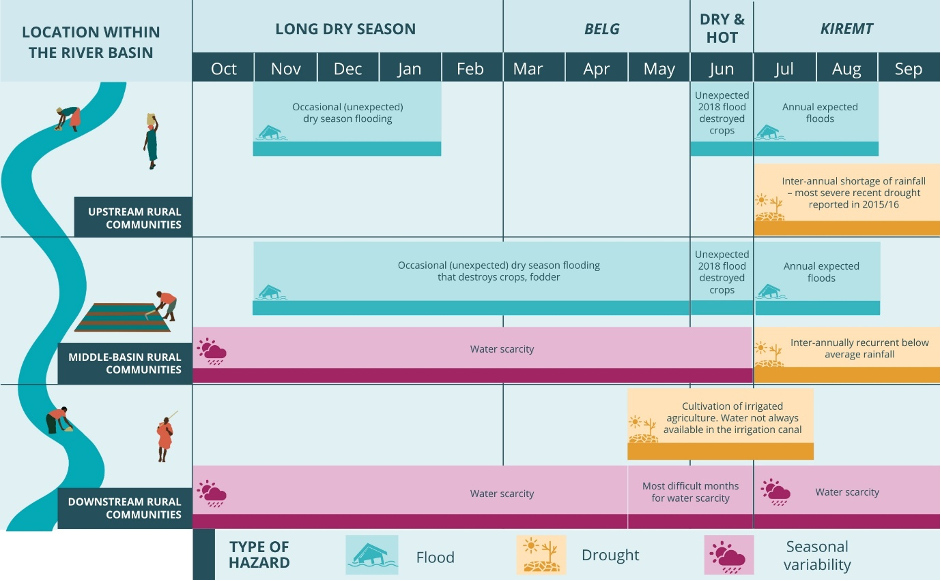

Reported temporal changes in recent extremes and recurrent water and climate-related hazards in the Awash basin, Ethiopia, caused by expected and unexpected climate and water resources variability that resulted in exposure and vulnerability to water risk. Water users in the downstream woreda reported rain commonly only falling in July and August and the middle basin user reported rain during kiremt only.

Putting society at the centre of climate change solutions

Climate risks are distributed unevenly between people and places. To build a climate resilient water future, the responsibility of mitigating these risks needs to be reallocated from the individuals and groups that are affected to the relevant national and local actors. For example, user groups differ in their capacity to maintain community waterpoints. This can result in the source being abandoned when the repair work is too costly or complex. However, if waterpoints within an area are managed as a network by a professional service provider, as demonstrated by FundiFix in Kenya, the risks can be spread evenly.

Many of the solutions for overcoming climate challenges live in the realm of the social sciences, and will be essential to realise COP26’s pledge to support those most vulnerable to climate change. However, only 0.12% of climate research funding is allocated to the social sciences. As three social scientists, we shed light on the lived experiences of water-related climate vulnerability to re-emphasise the importance of social research to ensure just outcomes in the fight against climate change.

Originally published on the REACH website