In this explainer, Dr Catherine Fallon Grasham breaks down the concept of climate resilience, what it is and why it is political. She argues for anyone working on climate resilience to keep power, politics and people at the heart of policy and practice.

Dr Catherine Fallon Grasham, University of Oxford

Within the context of the global climate emergency, climate resilient development has become the new paradigm for sustainable development. Climate resilience is gaining particular momentum in the water sector since water security is intimately connected to climate change.

Whilst the impacts of climate change are most visible in the natural environment, the causes, and effects, are rooted in human behaviour and political processes.

Climate resilience is inherently political – the negotiations that will take place at COP26 in Glasgow in November, alone, illustrate this. In a recently published article in Nature Partner Journal Clean Water along with colleagues, I offer insights on how to engage with power, politics and people in efforts to build climate resilience.

What is climate resilience?

Climate resilience is widely considered to be the ability to recover from, or to mitigate vulnerability to, climate-related shocks such as floods and droughts. However, definitions of climate resilience differ across sectors and scales and are often apolitical.

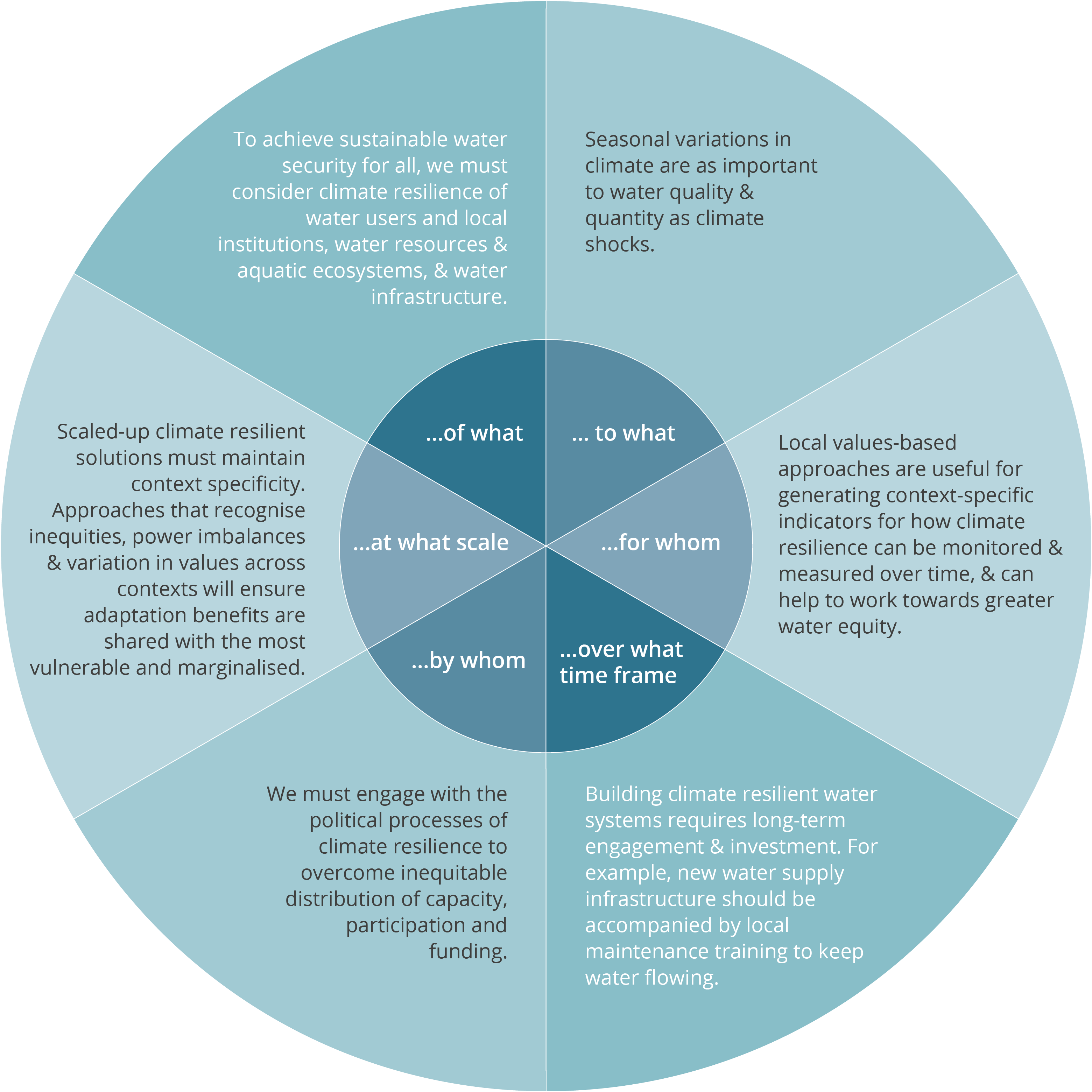

Apolitical definitions do not include who is responsible, who benefits, and how. Drawing on existing politicised definitions, such as in the IPCC 5th Assessment Report, we define climate resilience as: a political process that strengthens the ability of all to mitigate vulnerability to risks from, and adapt to changing patterns in, climate hazards and variability.

(Credit: REACH)

(Credit: REACH)(Credit: REACH)

Climate resilience is a political process that strengthens the ability of all to mitigate vulnerability to risks from, and adapt to changing patterns in, climate hazards and variability.

Why is climate resilience political?

Building resilience to climate hazards and climate variability requires politicised decisions about financing, inclusive decision-making and appropriate practice for equitable outcomes.

Financing

The poorest are most climate vulnerable, but serving and protecting them is more costly. In a positive move, the UK is doubling its International Climate Finance commitment to help developing nations with £11.6 billion over the next five years up to 2025/2026.

But, there must be shifts in how the development sector as a whole allocates funds. The current trend is short-term projects and a fear of engaging with uncertainty. However, there is added value in longer-term investments that address current climate variability and engage with uncertain climate projections.

Inclusive decision-making

Including diverse actors in decision-making processes can expose, and address power imbalances across scales. Meaningful engagement with the most vulnerable will go further towards sustainable change. Gendered approaches, in particular, are essential for building climate resilience, since women, men and children experience vulnerability and adapt to climate risks in different ways. Though necessary, disrupting the status quo by diversifying participation in decision-making processes across scales will be neither quick nor easy.

Practice for ethical outcomes

Existing socio-ecological resilience, and the context-specific values of marginalised communities, must be embedded in climate resilience. This is essential to prevent maladaptation – when adaptation strategies inadvertently increase vulnerability to climate change. Doing so will go a long way towards reducing inequities in vulnerability to climate risks.

Key take-aways

- Despite its rise in prominence, climate resilience is not a panacea; resilience carries different meanings across scales, sectors and society and it can only be relevant with a contextual perspective.

- In order to tackle inequities, and achieve the SDGs, more attention should be paid to contending with the political nature of climate resilience.

- The operation of climate resilience can have greater engagement with politics in six areas by asking resilience of what, to what, for whom, over what time frame, by whom and at what scale?

The npj Clean Water journal article referred to in this blog post was an output from a REACH-Oxfam GB co-hosted workshop in February 2020.

Originally published on the REACH website